In honor of the 71th Anniversary of D-Day, I’d like to post this story which I wrote for the News Journal in 2003. Here is my tribute.

A Salute to the Troop Carrier

Loose knots of men gathered beneath the sheltering wings of the Turf & Sport Special, the C-47 “Gooney Bird” displayed in the Air Mobility Command Museum at Dover Air Force Base. Wives, daughters, sons; extended family and friends pointed cameras and exhorted the men to stand closer together so no one would be left out of the pictures.

As one group finished, another took its place until those attending the “Salute to Troop Carrier,” the first National Reunion of WW II Troop Carriers, had their photo taken with the historic plane, identical to the ones on which they’d served in the European or Pacific Theaters of War.

The Douglas C-47, like the men, has a proud history. Together, the planes and men delivered troops and gliders into battle for Operations with names etched in history. They flew into North Africa for Operation Torch. Sicily for Operation Husky. The South of France for Operation Dragoon. Holland for Market Garden. They made the jump across the Rhine, Germany in Operation Varsity. And of course the most famous of all, they flew Operation Neptune, the Airborne Invasion on D-Day.

These names echo with the sounds of their combat missions in the European Theater. They do not include the Pacific Theater, their work carrying wounded away from the battlefields, or airlifting fuel deep into Europe to feed Patton’s insatiable tanks.

Bill Woznek, Bloomsburg, PA, the sole reunion attendee from the Pacific Theater, completed 390 missions; 119 combat missions, for a total of 1800 flight hours. Due to their shortage there was no rotation for Troop Carrier pilots, said Woznek. Bomber pilots and Fighter pilots usually served in the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) for about one-year or 300 flight hours. Troop Carrier pilots served the entire war.

Everywhere the 125 veterans gathered, they reminisced about pulling “double tows” of gliders into France or snatching a few hours of sleep under the wings of their planes while ground crews made hasty repairs before the flight crews returned to the skies.

Never Forget, Always Remember

Many people picture D-Day starting with a line of Allied ships breaking though the early morning fog as they approach the coast of Normandy. In reality, Operation Overload, the Invasion of Normandy, began in the dark morning hours of June 6, 1944, as the first of 821 C-47s dropped their Paratroopers and Pathfinders in France.

Walter Boyne, retired USAF Colonel and former director of the National Air and Space Museum, opened the panel discussion, The Truth about D-Day, with the comment “If you’re here today, you’re a lucky guy.”

The C-47s flew unarmed and unarmored. They did not have the self-sealing fuel tanks found on WWII bombers and fighters. When the Gooney Birds flew low, below 200 feet, to escape radar detection, they were easy prey for ground fire. Reunion attendees joked about returning fire from German troops with small arms through the open side door.

When the talk turned to D-Day, the discussion immediately focused on several key factors that contributed to the outcome of Operation Neptune; the bad weather over the coast of Normandy, the resulting break-up of some serial formations, the navigation problems, and the orders to maintain radio silence.

At first, everything went well for the Troop Carriers; formation flying proved easy in the clear dark sky over the English Channel. They flew in their traditional “V of Vs”; where three planes flew as a “V” and three “Vs” made nine planes. Eighteen planes, a squadron, assembled for one-purpose made a serial. For Operation Neptune, the C-47s traveled predominantly in serials of 36 or 45 aircraft made up of nine-plane “V of Vs.”

A C-47 tows a CG-4A glider.

The pilots relied on visual sightings to keep their tight formations. Within each “V” or wing, the planes flew 100 feet apart. At night, only three small blue lights glowed atop the wings.

These close formations were essential to mission success to prevent the wide dispersal of Paratroopers during their jump, and to locate their Drop Zones (DZs).

Once the Troop Carriers hit the coast of Normandy, disaster struck. At the assigned altitude of 700 feet, the Troop Carriers ran into a cloud bank so dense many refer to it as “The Black Cloud.”

Although the field orders for the “dress rehearsal” for D-Day contained specific precautions against bad weather, those precautions were left out on D-Day.

In near zero visibility, the pilots had to make decisions quickly or risk midair crashes and the loss of all lives on board. Some pilots climbed, getting above the clouds at about 2000 feet, others dove and broke out around 500 feet, some flew left, and others flew right. Miraculously, no collisions occurred.

The pilot’s difficulties had just begun. Many found themselves alone after they emerged from the clouds. No sight of their wing mates. Each pilot was on his own.

Only one-third of the planes had navigators. How were the remaining two-thirds to find the DZs or Landing Zones (LZs) for their Paratroopers or Gliders?

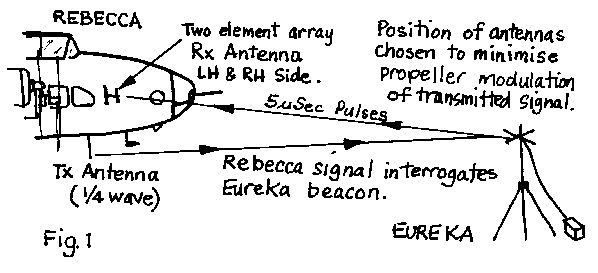

In an age of personal global positioning devices, it is important to understand the navigation technology which existed in 1944. On D-Day, the pilots relied on Rebecca-Eureka, a top-secret radar device used to locate the DZ. The onboard “Rebecca” receiver sent a signal to the “Eureka” ground transmitter, placed into position on D-Day by Pathfinder Paratroopers. If many planes in a formation switched on their Rebeccas at the same time, the Eureka could get swamped and send out a false signal, often indicating a DZ miles away. By limiting the number of Rebeccas, they reduced the chance of this happening.

Unfortunately, since some planes had been forced to break formation, the pilots without Rebeccas had to rely on visual sighting to locate their DZ. Pilots and crews searched the darkness for smokestacks, railroad lines, rivers, anything to help them find their DZ. Again, decisions had to be made quickly; they had roughly six or seven minutes before they should be over their DZ.

If the Pathfinders, the first serials that flew into Normandy, had radioed information about the cloud bank, perhaps alternate orders could have been relayed. But radio silence had been ordered; radio silence was maintained.

Pathfinder Paratroopers, hampered by ground fog, had difficulty positioning the holophane “T” lights, another navigation aid.

Movies have depicted the Troop Carrier pilots flying erratically to avoid flak. Somehow, the movies have ignored Lt. Marvin Muir of the 439th Troop Carrier Group, who received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) posthumously for holding his burning C-47 level so his 101st Airborne Paratroopers could jump. Muir’s crew died with him.

Pilot Don Skrdla also received the DSC for flying over the DZ three times when awkward bundles jammed the door before his Paratroopers could jump. According to Dr. John Warren in his book, AIRBORNE OPERATIONS IN WORLD WAR II, EUROPEAN THEATER, in spite of the weather and lack of electronic navigation aids, 35% to 40% percent of the paratroopers dropped that night landed within one mile of their intended DZ, while 80% landed within five miles.

In their first ever “Salute to Troop Carrier” Reunion, Dover Air Force Base Officers presented Commemorative Medals to the Veteran Crew members during an Awards Banquet.

The C-47, Turf & Sport Special also received a medal for its historic contribution.

The Air Mobility Command Museum

Dover Air Force Base

Dover, Delaware

www.amcmuseum.org

Portions of this story were published in 2003 by the News Journal under the byline of Gail A. Sisolak. All copyrights reserved.

Pingback: Chicago Boyz » Blog Archive » History Weekend — MacArthur’s Parachute Resupply in the S.W. Pacific